The Africa Development Bank has described African economies as “resilient and gaining momentum” with real output increasing to 3.6% in 2017 and likelihood of the growth accelerating to 4.1% in 2018 and 2019. How in your view is this economic growth likely to impact uptake of construction cranes and tower cranes in West Africa in particular and sub Saharan Africa in general?

Neither construction in general nor tower cranes in particular form a large part of the market for new equipment. Construction is a sector that is largely based on used equipment coming from outside the region. International contractors often purchase used equipment especially for their projects or relocate equipment from their existing fleets elsewhere in the world.

Where in Africa is the greatest demand for your mobile cranes? How about your tower cranes and what could be the key drivers pushing up this demand?

We operate in an area which is basically the ECOWAS region with a couple of exceptions – it is an area our technicians can travel in visa free so we can respond to needs anywhere at short notice. There is no particular single territory that we can point to that has higher demand over others. The main drivers for demand are international commodity prices that influence projects in mining or the oil and gas sector.

How has your range of crane products been shared among the construction, residential and commercial market segments in West Africa or in sub Saharan Africa? Which segment has been your greatest revenue generator and therefore accounting for a large share of your growth in this? Is this trend likely to continue in the long term you think?

A Paterson Simons supplied Konecranes Goliath crane, at a Gold Mine in Ghana.

Mining is the main sector that drives demand. Many years ago mining companies would move from an exploration to construction phase and at this point a contractor would often supply used equipment from outside the region for their project which ultimately would be left on site for maintaining the mine. The equipment was often old and poorly maintained. The challenges presented by this equipment often had a major impact on operations so there has been a growing realization that quality lifting equipment with good local support is needed from the day the mine is completed. These days most new sales go into to new mines or mine expansion projects. Mines are becoming more sophisticated in looking at long term maintenance of their plant and equipment and a range of lifting equipment is increasingly being specified at the design stage with overhead cranes, tower cranes, rough terrain, all terrain, pick and carry cranes and crawler cranes along with other types of lifting equipment like telehandlers can all form part of the plan for post construction maintenance. We play a role in helping getting that mix right.

The oil and gas sector is served by a growing number of quality rental companies who also need new equipment to satisfy demanding safety standards of the industry. Ports also invest for the long term with new equipment for handling project cargo.

Africa is one of the regions in the continent said to contribute least to the growing problem of carbon emissions but suffers most from the effects of climate change. How in your is the growing consciousness among governments in Africa on the problem of climate change shaping the growth in demand for advanced mobile and tower cranes and how has Paterson Simons responded to this trend?

Environmental concerns do affect us in one specific area: fuel quality is a major issue. To run a modern Tier 4 engined machine you need max 15 ppm ultra low Sulphur fuel which is simply not available. The UN publishes statistics on fuel quality and some of the worst fuel in the world is in West Africa – Sulphur limits are in excess of 2000 ppm. The tragedy is that much of this fuel has been deliberately blended down by international traders just make a few extra dollars. In 2016 knowledge about the practice got into the public realm and in the ensuing outrage three Governments (Cote D’Ivoire, Ghana and Nigeria) legislated to introduce a 50 ppm maximum mirroring a move made by countries in East Africa a few years ago. This is still not low enough to run a Tier 4 engine but is a radical improvement. In practice only Ghana has so far managed to implement the change – the upgrades needed to local refineries present a challenge also – but the consciousness is there and will not go away. Practically we have to continue to sell Tier 3 engined machines – and we cannot see this changing in the near future but the trend is going in the right direction. The paradox of improved emissions standards in the developed world is that it limits the age of used equipment that can be sold outside those areas: machines built after 2012 and sold into Europe and North America cannot be imported into West Africa – reinforcing the two standards and undermining the ability to replace older equipment in West Africa. Fortunately Grove have been working with engine manufacturers to develop downgrade kits for Tier 4 to Tier 3 – the process involves some legal documentation as well as physical changes to the engine – and we have now successfully delivered a few recent used units into the area.

Africa has been mentioned alongside Latin America as one of the markets that have potential for bigger growth post 2021. Do you share this view? What explains this high expectation on Africa’s mobile and tower cranes in the short and medium term?

I do agree and I think the main driver is simply that the market sector for quality equipment and service is quite small relative to other areas of the world but there is a growing acceptance that there is direct relationship between quality and productivity. An increased interest in safety will also drive growth. The quality market will get bigger regardless of how those individual markets perform although we expect growth from them as well.

From you experience of Africa’s cranes market, how can you describe the buying behavior of crane buyers in the region and what does this say about their view of these equipment products?

Most modern cranes, particularly all terrains because of their complexity, belong in hard working rental fleets which is still a fairly small sector particularly at the quality end of the market so many of our customers are owner/operators and not crane specialists. This does call for a fair degree of education on our part but we take pride in helping them make the right choice of equipment and have a full range of services to ensure they stay safe and productive after they have purchased the equipment. Safety devices and standards are not mandatory and typically manufacturers omit them (e.g.outrigger monitoring, third wrap indicators, 75% charts) to offer the cheapest product they can into the region. We believe strongly that this region of the world is probably the first place to need these devices not the last and do all we can to ensure customers are educated on these points at all levels.

What is your take on the current skill levels in Africa markets where you operate? How are you contributing towards the growth of the current and future pool of crane operators in Africa?

For our technicians we have invested a lot in building up a pool of strong local engineers – it is a long game starting at apprentice level – our only regret is that we cannot bring them through faster: training needs to work hand in hand with experience . One of my proudest achievements in business was seeing two of our local engineers reach Grove Master Technician level and we have more in on the way too.

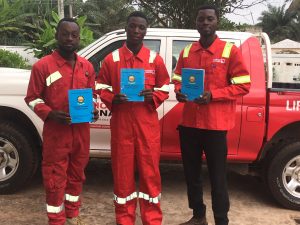

Recently, an in-house inspection training programme was concluded in Douala, Cameroon. DIT’s engineers were each trained on how to thoroughly inspect the Konecranes SMV 4531 TB5 Reachstacker, as well as the SMV 7/8 ECB90 Konecranes empty handlers.

In 2018 interns from TTU (Takoradi Technical University) spent 2 months on internship at Pasico’s Takoradi engineering office.

As Manitowoc dealers we provide on site operator familiarisation as part of the commissioning process for all equipment but we have long taken the view that given the investments made by our customers, particularly those for whom lifting is not a core activity, we need to do much more than that so we have a training division. For operators, rigger and lifting supervisors we can provide anything from hands on one on one operator training for an unskilled operator to certified classroom training for seasoned lifting professionals. We even run courses for managers or supervisors who need educating on basic lifting practices to help them understand their relationship with their lifting teams.

The skills are there but they need to be nurtured: knowledge transfer is a big part of the culture of our business.